I want you to imagine you’ve just spent two hours listening to some incredibly experienced academics raking over what is, in effect, your life experiences. That’s what I’ve just experienced at the launch of a book called Sharing Care. It’s a book that explores the experiences of men who either share the care of their children or, like me, are the main carers of their kids.

It was a slightly odd experience. Some of what was said mirrored my thoughts and experiences exactly. Some of it, I have to confess, made me feel uncomfortable because it highlighted some awkward truths I am only too aware of.

Being 2020, the book’s launch took place via Zoom and the event was chaired by Dr Ranjana Das, a sociologist with a particular interest in how technology and modern communication methods impact on family relationships (among other things). As highly experienced sociologist after highly experienced sociologist came forward and gave their thoughts on the book and the research behind it, I couldn’t help feeling this was like watching a very bizarre episode of the long defunct television show This is Your Life. I was half expecting a confused-looking stay at home dad to suddenly join the discussion so they could be presented with a copy of the book (yeah okay, that was my imagination getting the better of me, but to a greater or lesser degree what was discussed will be all too familiar to all stay at home dads or men who share care).

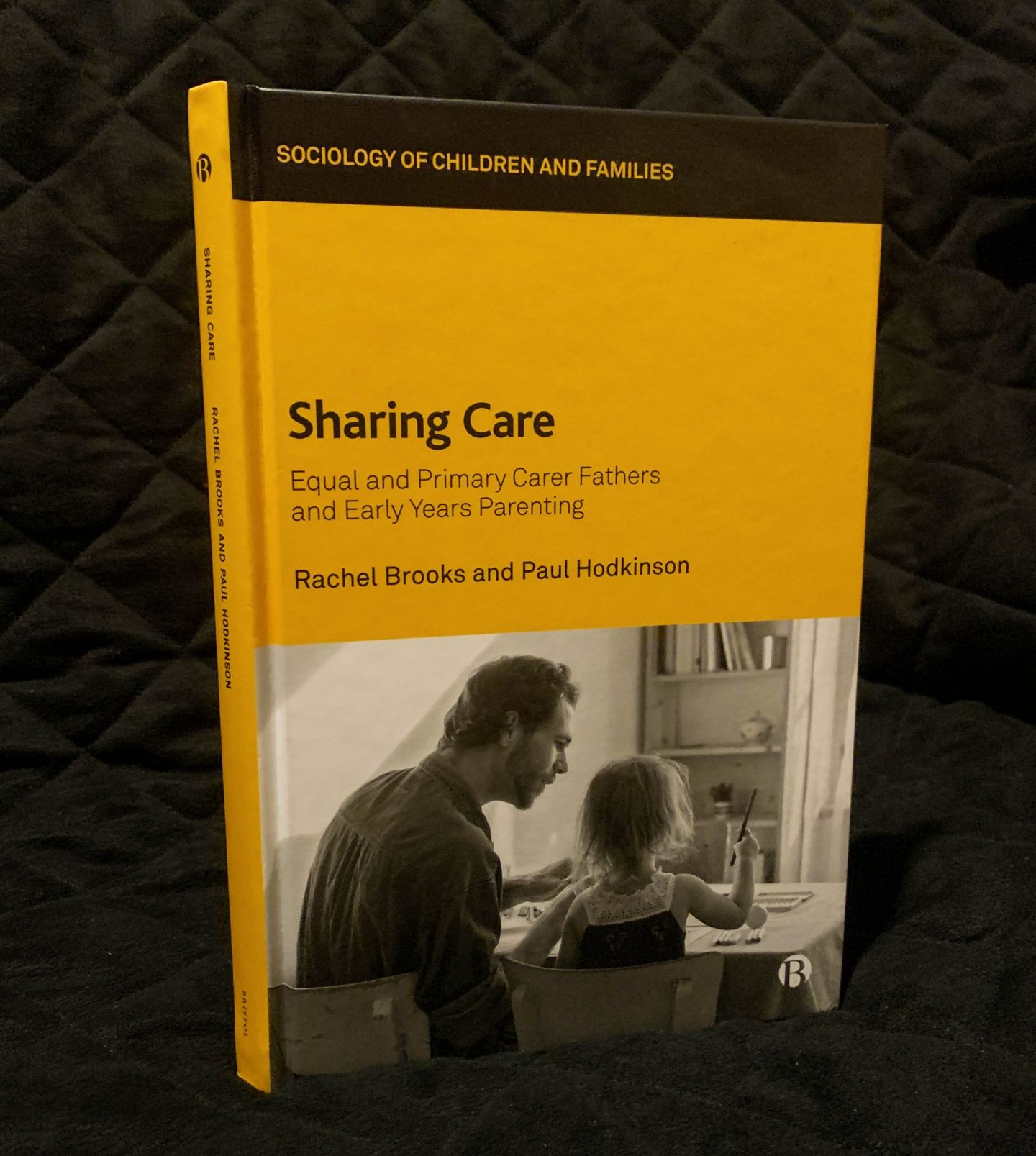

Sharing Care: What you need to know

The full title of the book is Sharing care, Equal and Primary Carer Fathers and Early Years Parenting. It’s been written by two sociologists from the University of Surrey: Professor Rachel Brooks and Reader of Sociology, Paul Hodkinson.

This isn’t a coffee table book. There are no photographs of topless, heavily tattooed millennials holding their babies. This is qualitative, academic research based on interviews with 24 men who, as stated at the start, are either the main caregivers for their children or share care equally with their partners (for the purposes of this research, the interviewees were in heterosexual relationships and both partners were resident with each other).

I was given a copy of the book earlier this summer. If you want to read about my initial thoughts, head over to my Instagram page where I put some words together (see image below). In this post I shall go over highlights from the book’s launch because it was fascinating.

Academic study versus my reality

As Brooks and Hodkinson spoke about their book, one word kept cropping up: Interchangeability. Just how easily did these men swap roles with their partners? Did they really take charge of family situations when they were called upon, or did they default to letting mum fulfil certain aspects of the parenting role?

The research suggested a certain disparity. Each couple was different, but generally speaking the men were fully paid-up carers within their own homes. Outside of the family home, be it the park or at parenting groups, these men reported feeling “out of place” and while many had tried to engage with parenting groups, they often gave up because they just didn’t fit in.

When it came to dealing with medical professionals, school staff or dealing with other parents (Brooks and Hodkinson didn’t say as much, but I took “parents” to mean “dealing with mums”) the default position was that mum would do these things. While highly involved fathers, there seemed to be limits as to how involved they could or would get.

Those uncomfortable truths I mentioned? Brooks and Hodkinson highlighted two of them in their discussions about interchangeability.

When I became main carer for my kids back in 2011, it was essentially a traditional gender role swap with my wife. My wife has never organised dental or opticians’ appointments for the kids, she’s never helped out a PTA-organised events or helped out on school trips and while she’s always helped with organising birthday parties etc. I’ve always done the lion’s share.

When I speak to couples who describe themselves as “sharing care,” I can figure out very quickly if that’s genuinely the case. I have a very simple test. I call it the Healthcare Test.

A father may be a wonderful, caring individual and he may be heavily involved in family life. If, however, he doesn’t know the address of the family GP, hasn’t organised six monthly dental check-ups or organised opticians’ appointments and accompanied his kids to them, then he isn’t part of a couple that shares care equally. To some that will sound blunt and harsh, but rare indeed is the father who handles these mundane tasks.

In fairness, Brooks and Hodkinson made the point that this pattern of behaviour starts very early in a family’s history. From before a baby is born, medical and health professionals often default to dealing with mum and once this pattern is set, it simply continues.

This is a very real issue. Some medical professionals do need to drop the unconscious bias. My personal experiences of dealing with the healthcare system have not always been the greatest, especially when my children were babies and toddlers.

Even so, there is a responsibility on fathers to play their part in changing the expectations of medical and healthcare staff. If dads don’t take their kids to see the health visitor, take their kids for inoculations, to the dentist or optician then this behaviour will never be normalised and will not be seen as masculine, fatherly behaviour.

Added to this, Brooks and Hodkinson said mothers are usually much more involved in parenting networks. This isn’t the case in my household. I am more involved with parenting networks than my wife, but I’d have to admit my involvement is cursory.

The reasons for this are once again spelled out in Sharing Care. Groups such as the National Childbirth Trust encourage women to socialise and form informal support networks. These groups continue at nursery and even the school gate.

If you have school aged children, just take a look at your class WhatsApp group of Facebook page. The male presence will be minimal and that’s because support networks for parents are almost always targeted at mums from the earliest days of a child’s life. Those patterns stick and men who are the main carers for their kids get left out.

In fact, membership of the class WhatsApp group and engagement on the school Facebook page are two additional measures I use to gauge how involved a man is with caring for his kids. These spaces should not be female-only zones but that will only change if men recognise their importance and engage with them.

There’s a further central theme to Sharing care. This was the ‘fatherly care horizon.’ This was the term Brooks and Hodkinson came up with to describe what fathers consider is feasible or appropriate for them to fulfil as carers.

Many of the issues discussed above can impact on a father’s care horizon. The horizons can also shift over time, not just as society progresses, but as children get older.

Other views on Sharing Care

Other sociologists were invited to give their opinions on the Sharing Care research. I can only give a brief overview of what was said as I had to break away from my screen from time to time. Professor Esther Dermott of the University of Bristol made some very interesting observations.

While this book was specifically looking at dads who share care in the early years, Dermott said there would be value in looking at how dads care for older children as they head into young adulthood. As it turns out Brooks and Hodkinson have plans to go back and re-interview the men in this study in the future. I personally feel this is vital as there is a gaping hole in academic research focusing on fathers who have older children.

Dermott also said that 10 years ago, men who were the main caregivers for their children were “unusual” but that these days such family set-ups were “less exceptional, but not commonplace.”

Andrea Doucet, Professor of Sociology and Women and Gender Studies at Brock University in Canada made an interesting observation. She said that “parental leave is not enough” to encourage men to do more of the caregiving and that the COVID-19 pandemic had bought attention to this.

Professor Tina Millar of Oxford Brookes University had a lot to say on the subject of care. She suggested we maybe need to rethink how we define care and caring roles and said a “desire to protect and care” is “ungendered.”

Miller also made a powerful comment about how the pandemic could get us all thinking differently about care and caring roles. She said:

“The pandemic has revealed how important caring is. We fit caring around paid work. We should fit work around caring but everything is the other way around.”

Valuable work but a second phase is necessary

I live the life of a male, main carer. Sharing Care confirmed many of my thoughts as opposed to teaching me anything new. For those who aren’t long-term male, main carers, Brooks and Hodkinson’s work will be enlightening and possibly challenging reading. That, however, is why it is so valuable.

I feel strongly that a second phase of research will be necessary. The interviews for the book were carried out in 2016. A second phase would shine a light on how these men have coped in their caring roles for a considerable period of time. Research on how men deal with the early years is very commonplace. Research on the middle and later years of childhood is very thin on the ground and a follow up to Sharing Care would be a valuable addition to an area of research where this is still much work to be done.

Added to that, the COVID-19 pandemic has turned the world upside down. While there’s lots of research showing men have been getting more involved as carers during this period, women have born the brunt of redundancies. It would be interesting to see what impact this has had on families.

I shall leave you with the one final thought. The next time you want to assess whether a man genuinely shares care with this partner, don’t ask about trips to the park, parents’ evening or doing the school run. Those are the basics of modern fatherhood and most men do these things. We need to push for greater involvement of men in the domestic sphere. The only way we’ll get there is if more men are encouraged to engage with parenting networks and healthcare professionals and so on. We need to get to a place where all fathers would willingly take and pass the Healthcare Test.

Sharing care, Equal and Primary Carer Fathers and Early Years Parenting by Rachel Brooks and Paul Hodkinson is widely available and published by Bristol University Press.