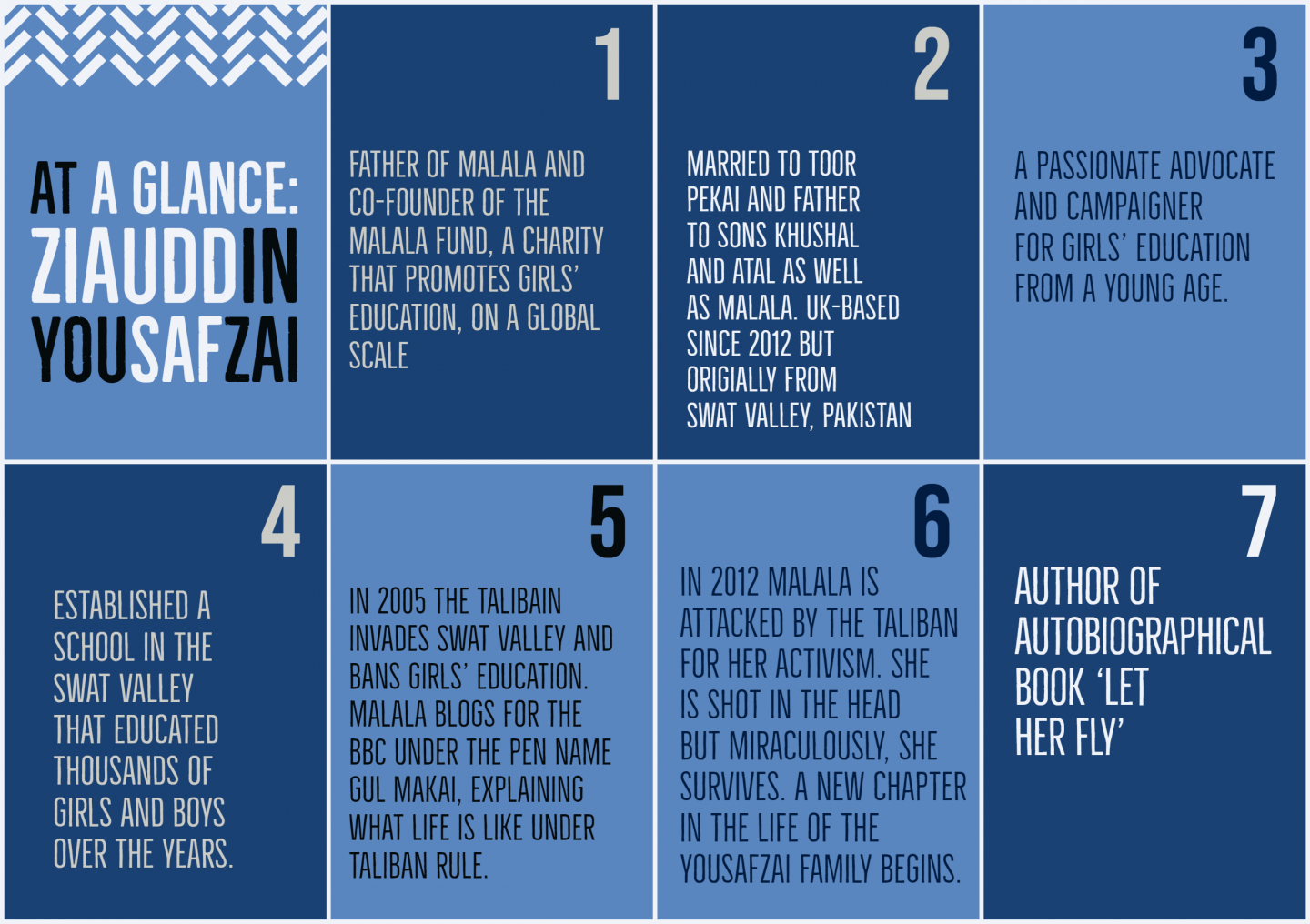

Asked to introduce himself, Ziauddin Yousafzai says: “Everyone knows me as Malala’s father.” You’d have to have been living somewhere very remote not to know of Malala, but in case you are that person, she is a young woman from Pakistan who survived after being brutally attacked and shot in the head by a Taliban gunman when she spoke up for girls’ rights to attend school.

A little while ago Ziauddin started following me on Twitter. I was flummoxed by his interest in me.

I knew exactly who he was because he had written the foreward to the most recent State of the World’s Father’s report. I knew he was the father of Malala, was involved with the Malala Fund and was a long-time education rights activist with a particular interest in promoting girls’ and women’s right to education.

I couldn’t resist approaching Ziauddin and asking if he would answer some questions as part of my Q&A series. To my amazement he agreed. Our schedules meant we could not meet up, but I sent him some questions. A little while later, I woke up to find he had sent me several voice messages.

I kid you not, there were almost two hours-worth of recordings. He’d answered every question with incredible care and warmth.

Along with his daughter Malala and the rest of his family, Ziauddin is a very inspiring character. It’s a real honour to publish this interview with him and I hope you find it as uplifting as I do.

Ziauddin, can you please introduce yourself and say a little about your work as an education activist and your role at the Malala Fund.

“I am from Pakistan and we moved to the UK and 2012 when Malala was attacked. I am a teacher basically.

“I was born in a teacher’s family. My father was a teacher and my brother was a teacher and I had also great passion to become a teacher. I started a school in 1994 and I started with three children.

“It was an independent school and when Malala was attacked, my school at that time had some 1,100 children: 500 girls and 600 boys. So that was my contribution to education as a teacher and an education entrepreneur in the Swat Valley. I was also involved in social activities like working for the environment, for peace and for eliminating poverty and was president of the Private Schools Association in the Swat Valley.”

Ziauddin explains his role changed when the Taliban took control of the Swat Valley.

“They changed my role from simply a teacher to somebody who was fighting for the right to an education, someone who became an education campaigner. When Malala was attacked and we moved to the UK, our lives changed and our role in education changed from a local level to the global stage

Commenting on the Malala Fund, Ziauddin said:

“I am the co-founder of the Malala Fund. We are working for girls’ education globally.

“Our mission is to see every girl receive 12 years of free, safe, quality education. The vision is that every girl should have a right to choose her own future.”

I understand you never saw your sisters’ names written down while growing up. Is this what inspired you to become an education and equality is activist?

“I grew up in a small village in the north of Pakistan in a typical patriarchal society and a very traditional patriarchal family. I grew up with five sisters and an older brother and I could see two sets of parenthood under the same roof in the same family. I can mention a few things.

“I could see I had milk cream with my tea in the morning breakfast while my sisters did not, because I was a boy. I had more clothes and pairs of shoes because I was a boy.

“The worst discrimination that my sisters went through was depravation of education. I was sent to school and my brother had been sent to school. None of my five sisters had an opportunity to go to school.

“I won’t blame my parents because even the government was patriarchal and there were hardly any schools for girls, though there were a number of schools for the boys. I could see that what made me different from others, what give me more opportunities was education. I think that if my sisters had received the same opportunities as I had, they might have done better than me.

“My parents had big dreams for me. They wanted to see me a doctor, to be a rich person, an influential person. For my five sisters, their only dream was to get them married as early as possible.

“I enjoyed being special but education changed me education transformed me into the kind of person right from my early like adolescent age.

“I was shocked at the age of 16 or 17 when I saw one of my cousins was bound in a forced marriage. She could not come out of that marriage because of the social taboos, the social norms and because of the stigma that was associated with divorce.

“If you ask that what changed me, my simple answer is ‘education.’ Education transformed me into the kind of person that I am. Education changed my inner being. It made my inner being beautiful. It gave me values, the value of empathy equality Justice truthfulness respect tolerance and patience.

“My sisters remained without education and I was determined that if I’m a father, the first thing I will do, I will give my daughter an education. So that was one of the reasons that inspired me towards girls’ education to work for girls’ education

“Education for girls is not simply learning mathematics, science subjects and languages. It is beyond that. It is emancipation. It is freedom. It’s giving them an opportunity to be themselves and to unlock their potential to pursue their potential to contribute to their own lives, to their family to their communities and to their countries. If we want to see equality and justice in our societies, we must impart quality education to other girls and boys.”

The key to gender equality has to be a good education. Would you agree with this?

“I think I have already answered this question, but let me highlight it further. The key to gender equality has to be a good education. Yes, quality education is a key to equality.

“If I had been an illiterate man of my society and if I had not had the opportunity to receive an education, I would have been stuck in patriarchy, badly stuck in patriarchy. I would have the same sick mindedness about women’s freedom and women’s empowerment and women’s rights.

“I would have believed in women as being a property or an object, something dependent on men in the control of men. What changed me? My one-word answer is ‘education.’

“Honour does not mean honour killing. Our honour does not mean to have control over women, the wives, sisters and daughters. Honour means respecting their freedom, in valuing their identity and giving significance and giving equal rights to them and equal respect to them.

Ziauddin explains that his school was a “platform for social change.” In addition to educating girls and boys he would hold consultations with parents, informing them they should encourage independence in their daughters.

“This is what I taught in my school and it was very very powerful. I’m so glad and I’m so proud that I was not only able to raise just one daughter who believes in equality and who is fighting globally for the women’s rights and girls right of education, but my two sons are also.

“I was able to raise feminist sons and not only my two sons but if you ask the boys of my school in the Swat Valley, if you have a chance to meet the girls who had been my students six or seven years ago, now they are graduates. You will know that their thinking is very different. They are very enlightened. They’re very brave.”

You’re well known for running a school in Pakistan, but where in the world do you think we need to concentrate right now when it comes to improving education, which locations have a particularly acute problem?

“We can mark four countries on the world map where the number of out-of-school girls is the highest. These countries are Nigeria, Pakistan, India and Afghanistan.”

Ziauddin explains the Malala Fund is working in all these countries, and also focusing on Brazil, Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon with a plan to expand operations in Ethiopia.

He adds that in each country, they have Gul Makai Champions. Gul Makai is the pen name used by Malala when she was blogging for the BBC (some of Malala’s blogs are still online). There are 41 champions in these seven countries and they are promoting girls’ education in their communities.

“The Gul Makai Champions work on projects for the promotion

of girls education. They are in contact with government. They are asking their

local governments and their national governments to invest more in education and

to improve and pass the laws which help girls and boys to be in school and to

have free access to quality and safety education.”

Is there anywhere in the world you feel we are going backwards and girls’ access to education is getting worse?

“It is a good question. So, 20 years ago, there were 200 million girls who were out of school. But right now, this number has reduced to 130 million girls. That means the population has increased while the number of out of school girls has decreased.

“Still, when we come to areas where girls access to education, is getting worse, it’s refugees. It’s a big challenge to reach the girls and boys in camps and to reach the population of internally displaced people in different countries like Syria and Afghanistan.”

Ziauddin explained there are, at this point in time, 60million displaced people in the world according to United Nations data.

“This is a population equal to the United Kingdom. The children in refugee camps have very poor access to education and especially the kind of education that is accredited by the host government. Their diplomas are sometimes not accepted.”

Ziauddin expanded on this, saying he visited the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan. He said the camp has 100,000 residents, 60,000 of which are children. Zaatari has only two schools and most of the girls were not receiving any education. Some girls were even being married off at a young age.

Other places with high refugee populations that Ziauddin has visited include Kenya, Rwanda, Lebanon and Kurdistan. In all these places, he said, a greater focus is needs on educating refugee girls.

The focus of the Malala Fund is on women and girls, but do you have any concerns about how boys are educated?

Before answering the question, Ziauddin explained the Malala Fund is a not-for-profit so must have a clear aim. That aim, he stressed, is the education of girls. He then said:

“Boys’ education is as important as girls’ education and the good thing about boys education is that governments, communities and parents prioritise it. They invest in the education of boys.”

This, however, leads to a “disparity” between the genders.

“I can give you one example from the Swat Valley. In one area of the Swat Valley there are 19 schools for boys, but only one school for girls. We need equity, girls should be on a par with boys in terms of opportunities and facilities for education, from primary up to the higher level of education.”

Ziauddin said the real challenge is not boys access to education, but the way they are often educated. A good education could change their outlook on the world.

“We need to have the kind of curriculum which changes the minds and hearts of our boys and inculcate in them the values of equality, the value of human respect for everyone, indifferent to their caste creed colour and gender and tolerance for the diversity of ethnicities of religion and so on.

“These are the beautiful things which boys and girls both should learn, but it’s very important that boys unlearn a lot of things which they have got throughout the history from their ancestors. We have to challenge patriarchy through the curriculum in every country.”

Patriarchy, Ziauddin adds, is not something that exists solely in the “East” and in “developing countries.” He says it can be found in developed countries also.

I don’t want this to all be doom and gloom. Can you highlight some success stories where Women’s education is improving and we are the Malala Fund has an impact?

“Yes, of course. I have a lot of great stories.”

Ziauddin said two Gul Makai Champions in Nigeria worked with the Governor of Kaduna State to pass a Child’s Rights Act. This guaranteed access to free, safe education to 80,000 children.

In Afghanistan, meanwhile, another Gul Makai champion has been working to train female teachers. Ziauddin said it can be a struggle in Afghan society to get parents to send their daughters to school. It’s harder still if the teachers are male. By having female teachers, parents are more willing to send their girls to school.

In a further project in Afghanistan, the Malala Fund is working with the Ministry of Religion and religious leaders. Ziauddin said they do “great things” educating girls in mosques, but by working with religious leaders, the hope is more parents will be encouraged to send their daughters to school.

Added to this, in the Yousafzai family’s home village in Pakistan, Malala invested money she was awarded for her Nobel Prize in a school (Malala is the youngest Noel Prize Laurette). The Malala Fund is also funding the project.

“In the village where I grew up, I never saw a girl going to school or saw a girl sitting next to me on the bench in school throughout my education. Now in that Village, there will be a state of-the-art school with the capacity to accommodate almost 900 to 1,000 girls.”

Ziauddin is true to his word. He lists many other achievements and the list is very long indeed. From school teachers encouraging children to undertake projects on Malala’s activism, to the many influential people she has met (President of France, Chancellor of Germany, President of Afghanistan among just a few). It turns out there has also been a sharp rise in children named Malala across the world!

He goes on to say there are two major barriers to girls receiving a good education.

“There are two big barriers to girls’ education. One is the social barrier and the other big barrier is financial. From my experience and knowledge through the reports that are shared with us by the Gul Makai Champions, there is not enough financial support for the education of girls. That is a bigger barrier than ‘social norms’ are.

“Then we have the cultural barriers. The interesting thing is that sometimes governments make it an excuse. They are not spending on girls’ education because the society doesn’t want girls to be educated. So ‘why should we invest on a school? Why should we build a school in an area?

“It’s kind of a lame excuse because we know that in many rural areas, they are patriarchal societies, but they are very very keen to send their girls to schools. They’re changing and changing very fast.

“We still have these social norms and like education is not as normal thing as it should be for girls, but with every passing day we see more awareness. We hear more encouraging stories. We hear that parents are Keen to educate their girls.”

I would like to change subject completely for a moment. Can you say a few words about what life was like for you under the Taliban when it overran the Swat Valley?

“It was like a horrible dream, like a nightmare, for my family and I. Before Talibanisation in the Swat Valley, we had a great, beautiful life. It was a peaceful place, a centre of tourism for decades. In every way it’s a great place and its history is very rich and its resources and natural beauty are matchless.”

Ziauddin explained how it all changed when Malala was around nine years old in 2005. With his background in education and promoting girls’ education, you won’t be surprised to hear he encouraged Malala to patriciate in every aspect of school life from debating to drama. When the school was closed, Malala’s parents would take her to school and she would act like a teacher, talking to the empty chairs.

When the Taliban arrived, everything changed. Ziauddin explained it thus:

“Our life completely changed and it was devastating when the Taliban emerged. They started an insurgency and in the beginning, they launched heinous propaganda campaign against girls’ education and also about polio drops that were administered to children.

“They gradually escalated their extremism and violence. In 2007 they started bombing schools and destroyed and burnt more than 400.

“They announced on FM radio that no girl, whether she is young or old, is allowed to go to school. The announcement was so threatening and so frightening that parents stopped their girls going to school.

“They were killing our notables and elders and I was the spokesperson for the Council of Elders of Swat Valley. I raised my voice for justice, for girls’ education especially. It was a very difficult time.

“We had suicide attacks, which killed hundreds of people and inflected inhuman atrocities on the people of the Swat Valley, which one can’t imagine. It was a nightmare. It was a dreadful dream, those years.

“I wish nobody to see such days, such conflict, such terrorism such, violence in their life. Peace is the most beautiful thing. Living in fear and living in terrorism is the most traumatic thing and just thinking of that in retrospect is very traumatic.”

There was of course the murder attempt on Malala’s life. How did you cope with the aftermath of that situation? It must have required Incredible strength of character.

Ziauddin said I may not have time or space to print all the detail. It was a very honest statement to make as regrettably space means I have had to paraphrase much of his response.

Before answering the question, he spoke at length about Malala’s early life. It is clear Malala meant a huge amount to him from the moment she was born. Having seen that Ziauddin’s father was unable to treat his sisters equally, he made it his “life’s mission” to ensure Malala received “equal treatment with boys.”

He said they are “travellers of this journey of life” together. He also told the story of a family member who turned up with a family tree shortly after Malala was born. The family tree only featured male relatives.

Ziauddin picked up a pen and added Malala’s details to it! The family member in question was not hugely impressed by this action!

You no doubt get the picture. Ziauddin has sons, but from a young age had been campaigning for girls’ right to receive an education in a society that didn’t always accept the idea. He was blessed with a daughter and had to put his beliefs into action. Then the Taliban came along with very different extremist ideas.

“When Talibanisation started in our Valley, I was one of the few people, social activists and human rights activists, who spoke against it. They say like father like son, in our home it was like father like daughter.

“I raised my voice and similarly at the same time, Malala also raised her voice. She wrote for a blog for the BBC and she wrote about the situation in the Swat Valley, especially about the girls’ education situation. She also volunteered for New York Times documentaries. She spoke to every platform, campaigning for girls’ education and this one girl was more powerful than the bombs, suicide attacks and rifles of the Taliban.

“She could not imagine to remain without education and to be illiterate. Education was her love.

“The Taliban wanted to finish her. When she was attacked on 9 October 2012, it was the most traumatic day, the most difficult day, most tragic day of our family’s life.

“I was feeling like I’d been swallowed up by a black hole. I forgot how to cry. It was such a difficult time.

“She was on the verge of life and death when she was attacked. We really didn’t know whether she will survive or not.

“I staunchly believe in my wife’s wisdom. The very day Mala was attacked, that night, I asked my wife ‘was it my fault that I didn’t stop her? Should I be responsible?’

“She was very clear. Emphatically, she insisted on telling me that I should not blame myself. I should not blame Allah or anyone because both of us raised our voice for peace and education and for Swat and we should not be ashamed of anything. We should not repent. We should not be regretful.

“Who violated her rights to education? They should be ashamed and should be repenting for what they did. My wife was a great strength during our struggle and after the attack. She was a great source of inspiration, help and support.

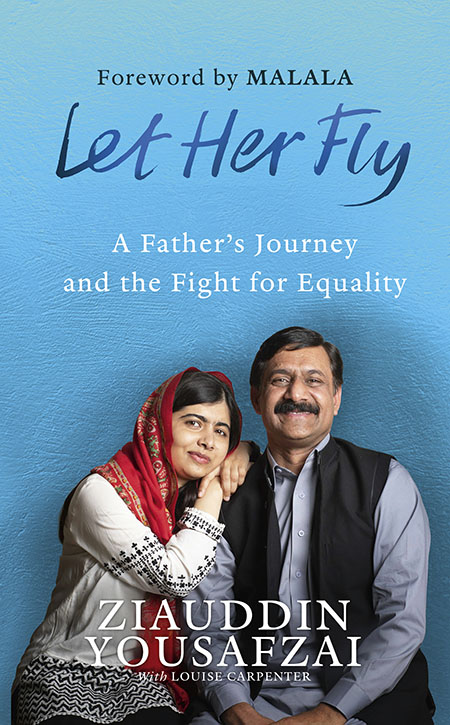

“To cope with the trauma, writing a book was very helpful (Let Her Fly, in which Ziauddin tells his life story and speaks about his work as an education activist). Also, Davis Guggenheim did a film on our life. It’s title is He Named Me Malala.

“Telling a story is also something that is therapeutic for your mind and soul and body. It helps a lot.

As for Malala’s future, Ziauddin explained she is studying Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Oxford University and is in her final year. She remains very committed to the work of the Malala Fund but whatever she chooses to do in the future, Ziauddin said he and and his wife will support her.

Final question, what does the future hold for you Ziauddin?

“This is a very good question, but I really don’t know what the future holds for me. I’m 50 years old. Half a century is already gone. That’s beautiful.

“I will be focused on my mission with Malala, working for girls’ education. I’m also involved in a lot of philanthropic work in the part of Pakistan where I grew up in my village and the adjacent areas like the north-west of Pakistan. I want to help many girls and boys in their higher education.”

Ziauddin admits he’d like to return to Pakistan and work within the community he grew up, saying he never imagined he’d end up in the UK. He said that option, for now, is “suspended” and that he’s only travelled back to Pakistan once since Malala was attacked.

He concluded by saying: “With that option suspended, this is a great opportunity that we are working for the education for girls globally.”

Inspirational words and more information

Hearing Ziauddin’s words was very inspiring. He and his family have been through so much and yet they have done so much for the world, especially promoting girl’s education.

I was genuinely touched at how much time and thought Ziauddin put into answering my questions. I was also fascinated to learn more about the work of the Malala fund. It’s a cause all right thinking people should support.

More information about the Mala Fund is available online. You can also donate to its amazing work on the website. The film He Named me Malala is available to view on Amazon and Netflix. Let Her Fly is available to buy from all good bookstores, plus from Amazon.

4 thoughts on “Q&A with Ziauddin Yousafzai, education activist & father to Malala”

Wow, this is incredible. What an inspiring family. We all have so much to learn from them about the difference one person can make to the whole world. I was aware of the Malala foundation but I had no idea how many countries they were working in or what a huge difference they were making. Thanks for raising awareness of it John.

Nat.x

Yes, inspiring is the word. Despite all the problems we have in the UK, Ziauddin has made me realise how lucky we are. Dealing with the Taliban must have been awful. That aside, at least out kids do have access to 12 years of free, safe, quality education. Think of those kids in the Zatarra camp. What future do they have?

What a moving piece. I’ve often wondered about Malala’s parents. She did so much at such a young age, that I thought there must be an incredible, supportive family behind her – and I was right. It must have cost her father a lot to stand against the patriarchy. The story about the family tree made me smile! Thanks so much for sharing this with us.

Thanks Nell, it is a very touching article isn’t it? Like you, I was in the dark about Malala’s family but having spoken to Ziauddin I can see they are all formidable characters. They are doing such amazing work with the Malala Fund and it was a real joy to speak with Ziauddin. It was great to read about how he fought for equality from such a young age and fascinating, if troubling, to her of how he and his family were forced to live under the Taliban.